Recently, I was visiting my middle-school cousins who have an arcade simulator that lets two players play a variety of classic video games (one like this). One of the games we played was called Puzzle Bobble. I don’t usually learn anything about business strategy from a ’90s arcade game, but the unintuitive winning strategy for this one made me question that assumption.

In Puzzle Bobble, players try to connect groups of bobbles (balls) by shooting new bobbles at the bobbles already on the screen. When three or more bobbles of the same color touch as a result of your shot, those bobbles disappear from the screen. If you free bobbles by popping all the bobbles that connect them to the ceiling of the game, they fall off of your screen and onto your opponent’s. The goal is to not let the bobbles fill your screen. The first player with a bobble crossing the bottom of their screen loses.

Here’s a demo from some random dude on YouTube:

(If you skipped over that video but do not fully understand how the game works, the rest of this post will make no sense. Please go back and watch the video. It’ll only take a few seconds to grasp.)

Obviously the way to win this game is to stack up a bunch of bobbles on the same single bobble then pop it and drop them all on your opponent, right? That way you can surprise them with a large number of extra bobbles and break whatever strategy they were working on. Through some experimentation, however, we found that this was not the most effective strategy. Too often trying to think ahead and factor the two player nature into your calculation led to a missed shot, unexpected new ball, or an unlucky string of bobbles. It was a much more successful strategy to stick to the basics and to focus solely on the goal of clearing your screen of bobbles. If you could take a clean pot shot at your opponent, you should take it (e.g. if the bobble after the current shot was going to free a tranche of bobbles, it was generally safe shoot your current bobble at the end of that tranche), but trying to drop the mother lode on them couldn’t be your primary strategy.

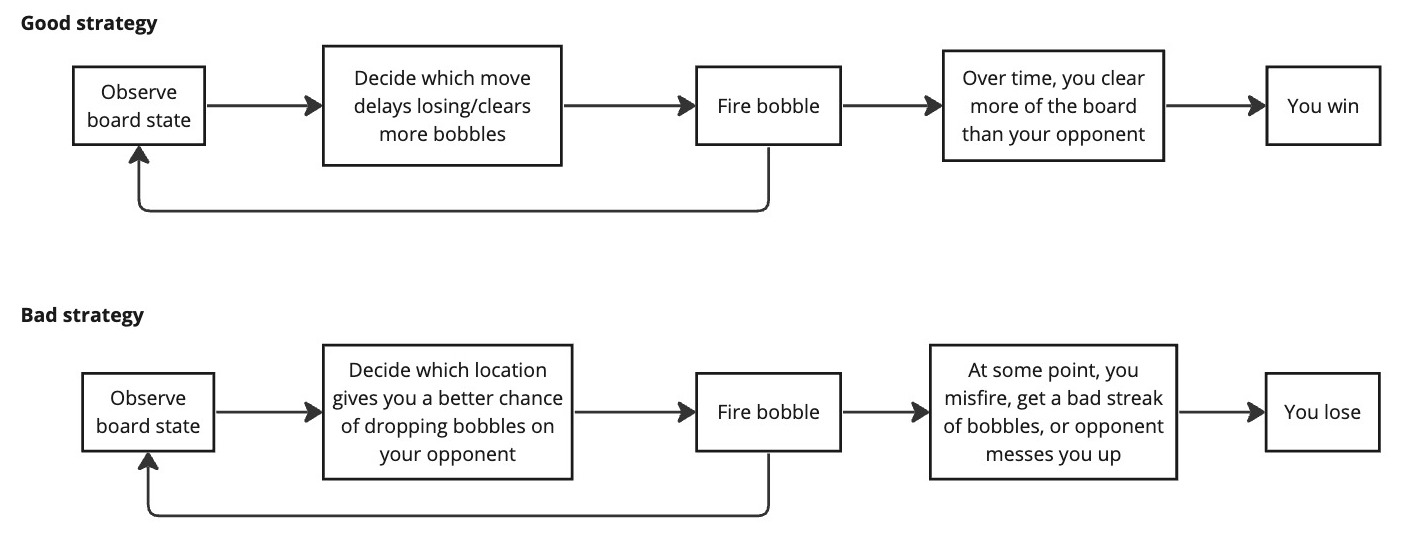

In other words, even though it was a multiplayer game, the best strategy was to ignore the other player(s) and execute well. In a diagram, the two puzzle bobble strategies look like this:

I saw the placement of each bobble as a strategic decision in Puzzle Bobble that contributes to your goal of winning the game, analogous to each business decision you make contributing to the overall strength of your business or product. Taking the strategy analogy one step further, maybe strategy should focus more on executing against core objectives than reacting to outside pressures. That stood in contrast to what I thought I knew about strategy - when there is more than one player in a game/market/etc., I thought you should treat the game as such. Strategy is supposed to be chess, or at the very least checkers, not solitaire.

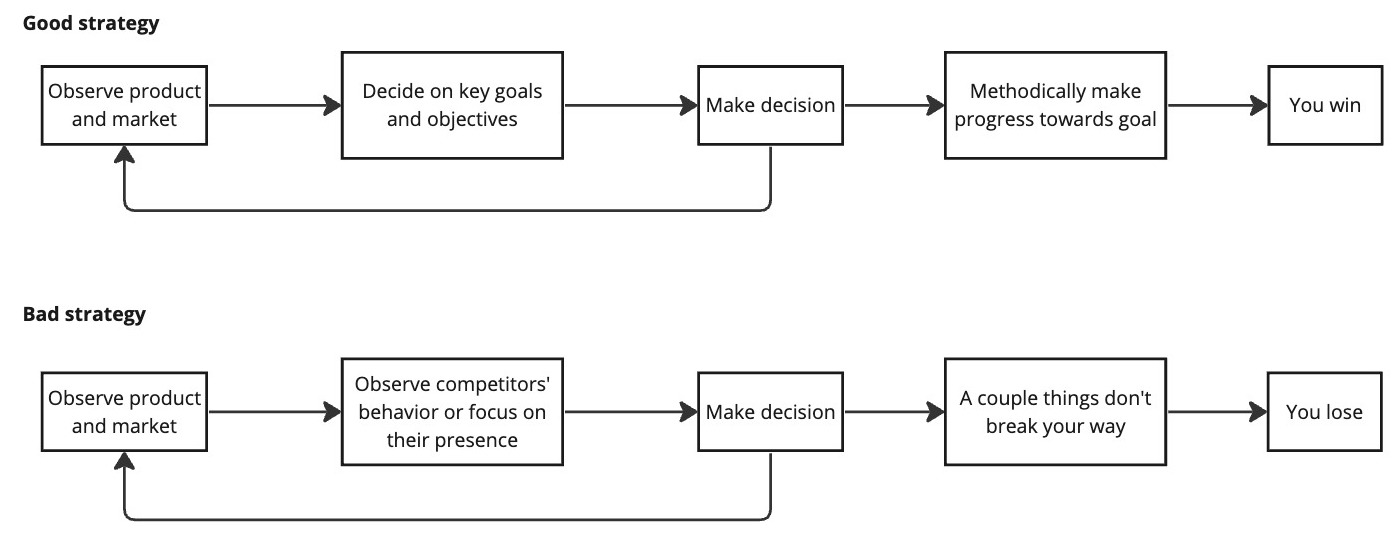

But, thinking back on my experience as a PM, even when I was working in markets with lots of competitive players like food delivery, the most successful features often were the ones that solved a clear problem as opposed to the ones that were aimed at our competitors. “Competitor X is doing Y” was almost always a preamble to a terrible idea. For example, “Doordash is bundling more (having the same driver pick up and deliver multiple deliveries at the same time), therefore we should bundle more” led to a worse outcome than “We have long delivery times when it is busy and many orders from the same restaurants go to similar locations (like college campuses), therefore we should bundle more under these circumstances.” Being competitor-aware and not competitor-obsessed applies to business strategy as well as product strategy.

In a diagram, the two business strategies look like this:

Similarly, if you look at Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers strategy framework - where the eponymous powers are scale economies, network economies, counter-positioning, switching costs, branding, cornered resource, and process power - only three of the seven (counter-positioning, cornered resource, and switching costs) require a second player and arguably that second player’s presence or strategies don’t influence your strategy except in the counter-positioning case. Most of them rely on a good set of objectives (e.g. increase affinity between nodes in our network, earn our consumers’ trust, etc.) rather than focusing on the fact that there are other players in the environment and figuring out how to mess with them.

I will note that this could be the wrong interpretation of the puzzle bobble strategy - maybe the takeaway should be that taking a large number of conservative bets (methodically clearing the screen) leads to better outcomes than risking it all on one grand plan (trying to build a large tranche to drop on your opponent) that could be easily foiled.

Shifting the focus from the competitive landscape to internal capabilities and customer needs can lead to a more robust and successful business strategy. Maybe business is like playing a game of Puzzle Bobble - it’s not just about the competition, but primarily about your performance. This is not to say that you should always think about strategy as a set of objectives to hit or tasks you must execute flawlessly, but that it might be wise to give some more mind share to that instead of constantly worrying about what your opponents are doing.

It also helps to be playing against 12 year olds.